Hydrogen Trucks Promise Zero Emissions: Sick of the road noise and pollution caused by semi-trucks barreling down the road near your house?

They could soon be harder to hear and healthier for you and for the planet.

The 3.7 million heavy-duty trucks that ship goods to consumers, haul raw materials across the country and transport components for manufacturers have long been powered by diesel engines that emit pollution and create significant road noise.

But an ambitious startup and several established automakers are promising to deliver hydrogen-powered semi-trucks that would create zero harmful pollutants, emitting only water vapor, and no engine noise but for the whirl of an electric motor.

The bottom line? Living next to a highway with trucks could eventually become a much more pleasant experience – but only if the promise of hydrogen fuel cells finally pays off after decades of development.

“They’re quiet. The emissions, the environmental impact, the noise – these are really great benefits for just the person that sees it on the road day to day,” said Yuval Steiman, director of corporate planning for Hyundai, which recently projected there will be 12,000 hydrogen trucks on the road in the U.S. by 2030.

That would represent less than 1% of heavy-duty trucks on the road.

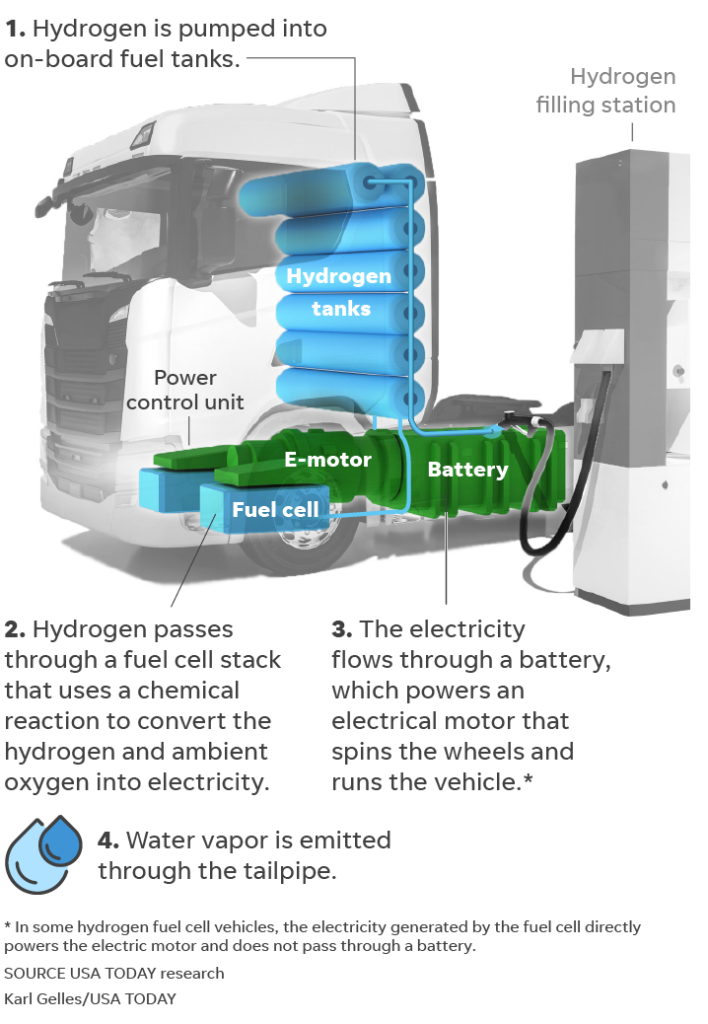

How a typical hydrogen vehicle works

Hydrogen vehicles run on electricity created through an on-board fuel cell that generates zero emissions.

For years, the technology made theoretical sense, yet a lack of hydrogen fuel pumps largely limited its reach. But advancements in hydrogen technology and an emphasis on beginning the technological rollout with heavy-duty trucks instead of cars is beginning to make fuel cell vehicles a reality.

RELATED: Why Diesel Engines Are Better Than Gas Engines

“Hydrogen, which never made sense to me as a consumer powertrain, makes complete sense as a heavy-duty commercial powertrain,” said Karl Brauer, an automotive analyst at vehicle-research site iSeeCars.com, referring to a vehicle’s engine and other parts that propel it.

The stakes for the truck manufacturing industry are significant: The sector is projected to have $27.5 billion in 2020 revenue, employ more than 25,000 workers and pay $1.7 billion in wages, according to research firm IBISWorld. A shift in powertrains could require the industry to overhaul how it sources components, hires workers and meets regulatory standards.

Several companies are driving the trend, including:

Toyota

The Japanese company is the leading seller of hydrogen cars in the U.S. with the Toyota Mirai, midsize sedan starting at around $59,000. It sold more than 1,500 units of the vehicle in 2019, mostly to customers in California who live close enough to hydrogen fueling stations to make it feasible. The 1,500 units sold represent a fraction of a percent of the total vehicles sold in the U.S.

Now, the company is moving into semi-trucks. Earlier this month, Toyota announced a deal with truck maker Hino to jointly develop hydrogen fuel cell trucks for the North American market. The trucks will get the Toyota Mirai’s hydrogen fuel cell technology and Hino’s vehicle body, with plans to deliver a “demonstration vehicle” in the first half of 2021.

That deal comes after Toyota in 2019 announced a separate collaboration with Kenworth Truck to develop heavy-duty hydrogen trucks for North America.

“We’re at that tipping point,” said Andrew Lund, chief engineer of heavy-duty trucks for Toyota. “The technology has proven to be available.”

Hyundai

Like Toyota and Honda, Hyundai has been working on hydrogen fuel cells for years, including recently selling the technology as the Nexo SUV, which starts at about $59,000 and gets 350 miles on a tank of hydrogen.

Earlier this month, the Korean automaker announced it had delivered the first units of its new hydrogen-powered heavy-duty truck, the Xcient, to customers in Switzerland. The company expects to ramp up production capacity of 2,000 units per year by 2021 with plans to bring hydrogen trucks to the U.S. through a $1.3 billion investment in hydrogen infrastructure here.

Hyundai expects to become “the world’s first company to mass produce heavy-duty fuel cell trucks,” Steiman said. “We have the vision of this hydrogen society and we think this is bigger than cars, this is bigger than trucks. This is really a power source that can have a lot of implications for the future.”

Volvo, Mercedes-Benz maker Daimler

The two automakers in April announced a joint venture to make hydrogen fuel cells for heavy-duty trucks and other purposes.

Earlier this month, Daimler revealed a hydrogen fuel cell concept vehicle called the Mercedes-Benz GenH2 Truck, saying it would be able to travel up to 621 miles on a single tank.

Daimler said it expects to begin customer trials in 2023 and enter production in the “second half of the decade.”

Nikola and General Motors

This upstart Phoenix-based Nikola made a splash this year by arranging a deal to go public and reaching a tentative manufacturing and technology partnership with GM. The startup has promised to deliver two hydrogen-fueled heavy-duty trucks, the Nikola Two and the Tre, within the next few years.

Nikola founder Trevor Milton predicted to USA TODAY in 2017 that diesel trucks would no longer be available for sale within 10 years.

But the company has faced increasing skepticism in recent months amid questions about the legitimacy of its plans, leading to concerns that it may not finalize its deal with GM, which is up in the air while negotiators rework their deal.

Short-seller Hindenburg Research published a report accusing Milton of orchestrating an “intricate fraud” with the company, saying that many of its claims were exaggerated or purposely misleading.

Soon after the report, Milton, who has denied those accusations, left the company, which is now facing multiple investigations by the federal government, including one by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The next Tesla?

Despite its troubles, Nikola’s emergence has reminded automotive industry observers of how Tesla exploded onto the automotive scene more than a decade ago, promising new electric-vehicle technology and pledging to revolutionize transportation.

Skepticism about Tesla eventually gave way to a recognition that CEO Elon Musk’s penchant for bombastic proclamations on social media did not change the fact that Tesla’s design and engineering prowess was legitimate. Tesla is now the world’s most valuable automaker in terms of total value on the stock market.

But can Nikola replicate that model for success?

Nikola CEO Mark Russell, who has been charged with helping to stabilize the company following Milton’s exit, said Nikola’s model of installing hydrogen pumps for customers, selling them the fuel and leasing them the truck as one complete package will help the company prevail.

He told USA TODAY that Nikola has “the potential to show the world that hydrogen can be a cost-effective fuel for long-haul trucking” and the company will “prove that in the next several years.”

But Nikola’s success may be predicated on whether it can seal the deal with GM or find an alternative manufacturing partner.

“We don’t have any ambition of trying to do everything ourselves,” Russell said. “We’re taking the path of partnerships.”

If Nikola is successful, that could help popularize hydrogen trucks, which would be “good for everyone,” Toyota’s Lund said.

But “our strategy is different,” Lund said. “They’ve been outspoken about what they’re going to do. Our culture is to explain to you what we’ve done.”

Russell said he’s been studying Toyota’s success for two decades. “Some of the smartest-led organizations in the world are pursuing hydrogen-fueled vehicles,” he said. The fact that “some of them are also working on hydrogen infrastructure is a validation of Nikola’s plan.”

Why now?

For years, the joke in the automotive industry has been that hydrogen cars are always 10 years out – but a decade passes, and they’re still 10 years out. Put frankly, hydrogen cars simply haven’t yet made a dent.

So what makes hydrogen so much more promising for trucking than for passenger cars?

Quite simply, it’s fueling infrastructure. Trucking companies and shippers can plot out their fueling plans by installing hydrogen fuel stations along fixed shipping routes, usually locating them at their regular stops or vehicle maintenance areas. That way truckers don’t have to hunt for hydrogen fuel in the wild, which is effectively impossible to find right now except for a cluster in California.

“You know where to put the stations,” Lund said. “We already see the truck routes.”

But Lund argued that traditional fuel stations that currently sell gasoline and diesel will eventually find it enticing enough to install hydrogen tanks too.

“We already have a fueling infrastructure throughout the world,” he said. “It’s just a matter of changing it out. It all depends on the adoption rate.”

Some remain skeptical, particularly about Nikola.

Hydrogen is simply still too expensive for most shippers to justify investing in fuel cell trucks, said Peter McNally, global sector lead for industrial materials and energy at investment researcher Third Bridge.

The average price of hydrogen for vehicles in California was $16.51 per kilogram, according to a 2019 government report. But the price is dropping quickly – and Nikola’s Russell said the company can deliver hydrogen for $2.50 per kilogram, which he said is about equivalent in energy to a gallon of diesel fuel.

Government mandates like California’s recent announcement that it’s banning gas-powered vehicles by 2035 will also help drive the costs lower, Russell said.

“You’ve got jurisdictions all over the world actually – cities, counties, provinces, states, and even nations are putting outright bans on fossil fuels on their books,” he said.

Follow USA TODAY reporter Nathan Bomey on Twitter @NathanBomey.